Why I Hid My Giving from My Co-Workers

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

As a giver at heart, I’ve always had a keen eye to show others I cared by finding ways to cheer them through my act of giving. Whether that be going out of my way to fix a problem or by offering little gestures, such as making a resident a snack or giving a resident their favorite candy. I would use my giving heart to build a relationship with them.

Some ways I tried to show the resident I cared for them included baking them cookies, making them a sandwich, buying them a board game, or getting one resident enzyme lotion. However, no matter how small the deed or inexpensive the gift was, the staff was irritated as hell and upset at me because I demonstrated to the residents a little act of kindness.

I didn’t understand why for a long time until it finally clicked. Deep down, the staff believed the residents didn’t deserve it! So in order to prevent my coworkers from getting mad at me, I hid it! I developed the attitude of “The less they know, the better!”

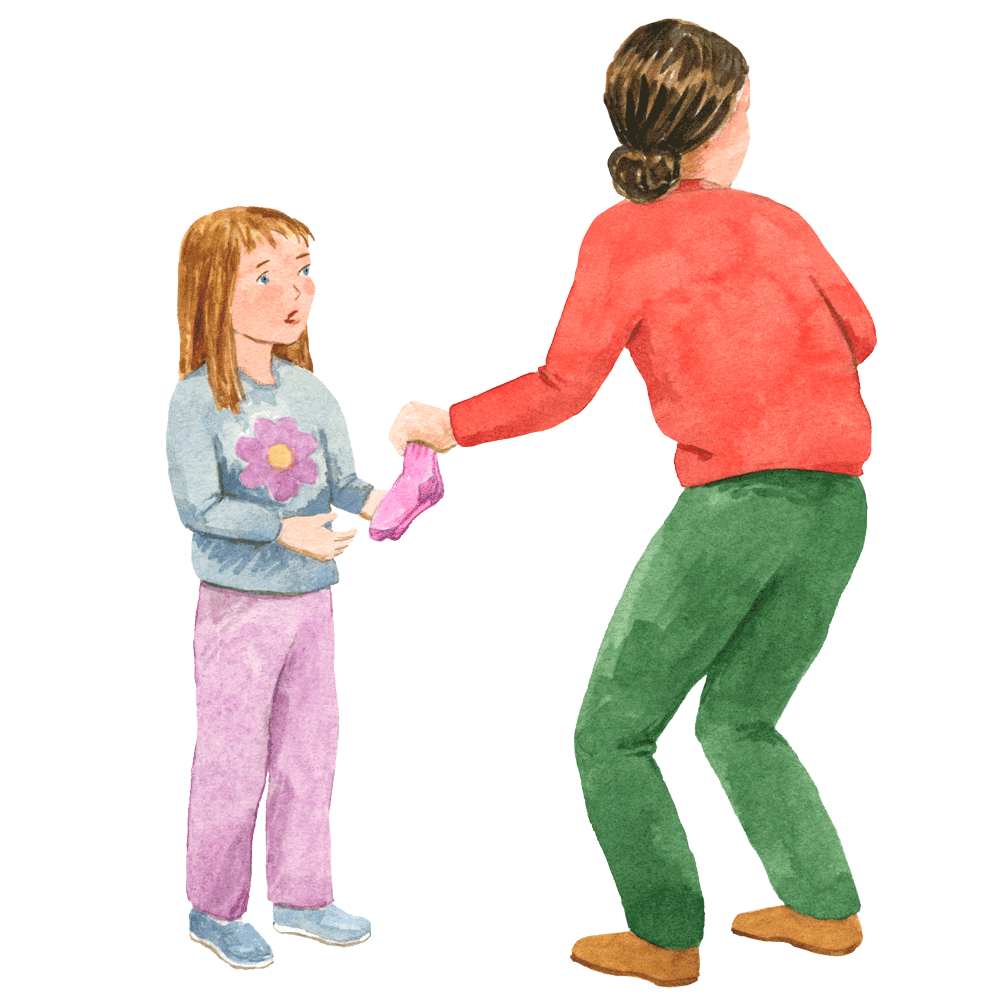

I hid my snacks in my sweater sleeve or in my backpack, never letting staff see whatever I was giving to the residents. I would wait till my co-workers left, grab whatever it was inside my backpack, hid it under my sweater sleeve (if it was small enough), and hustle to their rooms to place it under their pillow or inside their backpack. I prayed they didn’t ask, “Who gave this to me?” Many times I would tell them before they found out so they didn’t have to ask that question.

For larger items, I would wait till everyone was out of the cottage to place it inside their room or inside the rec room. Things like DVDs, books, puzzles, and teddy bears. And if I was by myself with a resident, I would say, “You didn’t get this from me or I will get in trouble!” And they understood. They would hide whatever it was I gave them.

When staff did see, they would ask: “Where did you get this?” The residents would say, “My friend from school gave it to me.” Everything I gave had to be out of sight. Because what my coworkers didn’t know wouldn’t upset them.

Some ways I tried to show the residents a kind act included:

- Baking cookies (told by my supervisor not to bake for them again, because the staff are complaining)

- Making them a sandwich (told by my supervisor, “They don’t deserve gourmet meals.”)

- Buying every resident the same Christmas gift (told by my supervisor, “That wasn’t good. You and I are going to have a talk,” which never happened)

- Bringing a board game from home (told by my coworkers, “Do not buy anything for the residents.)

- Buying them a DVD player (given stern looks by my coworkers)

- Buying a resident Enzyme lotion (told by my coworker, “Do not buy anything for the resident’s.”)

- Buying them Starbucks or fast food (told by my coworker, “Do not buy anything for the residents.” After returning from a medical or court appointment. I made sure they finished their food, before dropping them off in front of the cottage.)

Why should a child be on level to get socks or school supplies? That’s a form of manipulation in order for that child to believe “if I want something from my cottage mom, I have to be on level.”From the adult’s perspective, they want the child to listen, follow rules, and clean their room because if they’re going to want something from them, they’re going to have to give them something in return.

In other words, “if you’re easy money, if you make my staff happy, and if you give me no problems then when you knock on my door, I’ll listen.” On a side note, even when residents followed their program, who was on level, and still when they asked the cottage mom for help, didn’t get it right away, were given excuses, or just not helped!

The cottage mom made that very clear that when she wanted to help you it had to be on her time and her schedule. She made sure that the residents knew who was in charge and if they gave her any attitude or any reason to not do something, she wouldn’t help them. Even if it was necessities like socks, school supplies, or enzyme lotion.

So why would staff believe a child in a residential treatment center didn’t deserve Starbucks or a board game? Staff believed if these children were in group homes, “then what did they do to deserve to be here? Obviously they acted out, had bad behavior, or were addicted to drugs, or why else would they be here?”

Just over 400,000 American children live in foster care, and some 55,000 reside in group homes, residential treatment facilities, psychiatric institutions and emergency shelters. This type of placement—called “congregate care”—may be beneficial for children who require short-term supervision and structure because their behavior may be dangerous.

However, many officials believe that children who don’t need that type of intense supervision are still in these group placements—depending on the state, between 5% and 32%—making it harder to find them permanent homes and costing state governments three to five times more than family foster care.

In fact, two out of five foster children in congregate care are without a clinical need, mental diagnosis, or behavior problem.

The kids weren’t “dangerous,” yet staff truly and deeply believed the residents were on a one-way ticket to jail, were sociopaths, and little monsters in the making. Staff justified their aggression and actions by treating the residents cruelly because they believed when they were going to exit care, the residents were going to be predators.

And keep in mind we knew nothing about any child’s case when they entered our cottage. We never read any reports, never spoke to their social worker, or were told why a child was originally placed in our facility. The staff just made accusations and assumptions that these children had to be here for bad behavior because who they were as individuals were bad kids.

Let me make this clear, the staff were the perpetrators, not the children. Staff devalued the humanity of their victims referring to the children as dangerous, lazy, dishonest, and violent. How did staff vilify the children? Every day I heard my co-workers use smear campaigns and hate propaganda to vilify the children in our residential treatment center. It’s sometimes said that people are demonized when they’re not recognized as individuals.

This happens when they are treated as numbers, near statistics, hogs in a bureaucratic machine, or exemplars of racial, national, or ethnic stereotypes, rather than as unique individuals. When a group of children is demonized, especially marginalized children with no parental figures, they become mere creatures to be managed, exploited, or disposed of, as the occasion demands.

I believe congregate care has gotten away with this because congregate providers isolate the children, cutting them off from the community, and keep their identity anonymous(not as individuals) so that the public isn’t aware of how they denigrate or stereotype them as dishonest, violent, and/or “bad” kids.

Ordinary people, like you and me, simply doing our jobs—whether that be a residential treatment counselor, case manager, or campus supervisor— without any particular hostility on our part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process. Moreover, even when the destructive effects of our work become patently clear, and we are asked to carry out actions incompatible with functional standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.

This is why we believe children who live in an institution will never receive dignity or high-quality mental health care because inpatient care can easily become a place where children are further traumatized, oppressed, or abused.

Works Cited

Smith, David Livingstone. Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others. First, St. Martin’s Griffin, 2012. (p. 27, 128)

“Congregate Care, Residential Treatment and Group Home State Legislative Enactments 2014–2019.” National Conference of State Legislatures, 30 Oct. 2020, www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/congregate-care-and-group-home-state-legislative-enactments.aspx.

Chadwick Center and Chapin Hall. “Collaborating at the Intersection of Research and Policy.” Chapin Hall & Chadwick Center, 2016, p. 5, www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/effective_reduction_of_congregate_care_0.pdf.